The Druid Deep Dive, Episode 6: JP Morgan's 1907 liquidity crisis: when there's no one to lock the bankers in the library

In 1907, JP Morgan locked bankers in his library to halt a panic. On October 10, 2025, $19 billion in crypto liquidated in hours—with no one to coordinate rescue. Explore what trust company runs and DeFi cascades teach about leverage, liquidity, and building portfolios that don't need saving.

The night the money stopped

On the evening of October 22, 1907, the third-largest trust company in New York City ran out of cash. The Knickerbocker Trust Company paid out $8 million to panicked depositors in just three hours before closing its doors forever [1]. The next morning, lines formed at trust companies across Manhattan. Within days, the contagion had spread nationwide, triggering what Federal Reserve historians call "the 8th-largest decline in U.S. stock market history" [2].

The crisis had roots in a spectacularly failed scheme. Two speculators—F. Augustus Heinze and Charles W. Morse—had attempted to corner the market on United Copper Company stock. When the scheme collapsed, it exposed the fragile interconnections between their banks, the trust companies that funded speculative lending, and the broader financial system [3].

Trust companies occupied a peculiar position in early 20th century finance. They operated with far lower reserve requirements than national banks—sometimes holding as little as 5% cash against deposits versus 25% for regulated banks [4]. They couldn't access the New York Clearing House's emergency facilities. And they had grown explosively: trust company assets increased 244% in the decade before 1907, compared to just 97% growth for national banks [5].

These "shadow banks" of their era provided crucial liquidity to Wall Street through a mechanism called call loans—overnight lending that financed securities purchases. Brokers would borrow from trusts, buy stocks, then pledge those stocks as collateral for call loans from national banks. It was leverage stacked on leverage, and it worked beautifully until it didn't [6].

When depositors began withdrawing from trust companies, the trusts had to call in their loans to brokers. Brokers, suddenly starved for credit, were forced to sell securities at any price. Stock prices collapsed. More trusts faced runs. Call loan interest rates spiked to 70% as liquidity evaporated entirely [7].

The man in the library

Into this chaos stepped a 70-year-old banker who had seen panics before. J.P. Morgan had helped rescue the U.S. Treasury during the 1893 crisis, and he understood something his contemporaries did not: in a panic, selective intervention matters more than blanket rescue [8].

Morgan returned to New York from a church convention in Richmond on October 19, summoned by urgent telegrams describing the unfolding disaster. He immediately began triaging institutions—examining their books, calculating which could be saved and which were beyond help [9].

His decision-making was ruthless and deliberate. Morgan let Knickerbocker Trust fail after his lieutenant Benjamin Strong examined the books and deemed it insolvent [10]. But when the Trust Company of America faced its own run on October 23, Morgan judged it worthy of rescue. He organized emergency loans of $8.25 million from other trust company presidents to keep it open through the next day [11].

The most dramatic intervention came on the night of November 2. A major brokerage firm, Moore & Schley, was about to collapse under the weight of loans collateralized by thinly-traded Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company stock. If Moore & Schley failed, the forced liquidation of TC&I shares would trigger another cascade [12].

Morgan summoned the presidents of New York's leading banks and trust companies to his private library on Madison Avenue. He locked the doors and refused to release them until they agreed to provide emergency funds [13]. By dawn, they had pledged the necessary capital. Morgan personally convinced U.S. Steel to acquire TC&I, removing the troubled collateral from the system entirely—and extracted a promise from President Theodore Roosevelt not to pursue antitrust action against the merger [14].

The New York Clearing House issued $110 million in clearinghouse loan certificates—essentially emergency currency that banks could use in place of cash [15]. Nationally, nearly $500 million in currency substitutes circulated before the panic subsided [16]. Morgan, Rockefeller, and Treasury Secretary Cortelyou had, through force of will and personal wealth, performed the functions that would later belong to the Federal Reserve.

October 10, 2025: the cascade with no Morgan

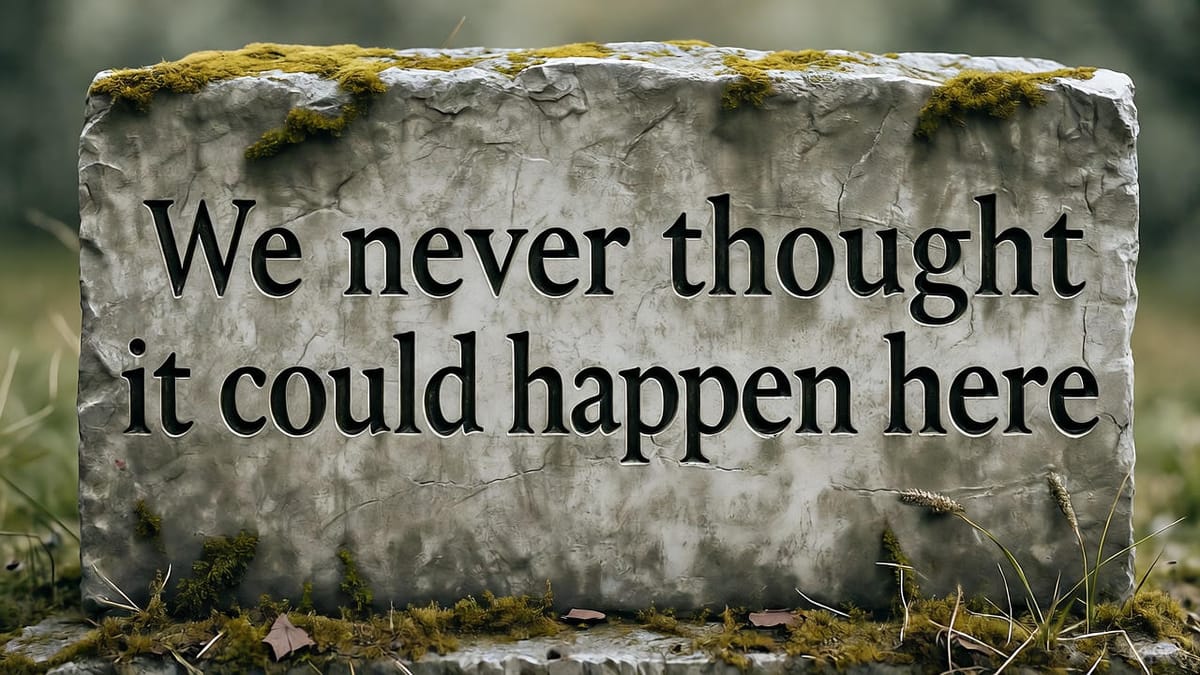

One hundred eighteen years later, cryptocurrency markets experienced their own version of the 1907 Panic—but with a critical difference. There was no one to lock the bankers in the library.

At 20:50 UTC on October 10, 2025, President Trump announced 100% tariffs on Chinese imports. Within hours, $19.13 billion in leveraged cryptocurrency positions were forcibly liquidated—the largest such event in the asset class's history [17]. Over 1.6 million traders were liquidated, and roughly $370 billion in market capitalization evaporated [18].

The structural parallels to 1907 are striking. Just as trust companies operated outside the regulated banking system with lower reserves and no access to emergency facilities, cryptocurrency exchanges and DeFi protocols operate outside traditional financial regulation with no lender of last resort [19].

And just as trust companies provided leveraged liquidity to stock speculators through call loans, crypto exchanges offered perpetual futures contracts with leverage up to 100x—positions that could be liquidated instantly when prices breached predetermined thresholds [20].

The mechanics of collapse followed the same pattern. When prices dropped, automated liquidation engines began closing leveraged long positions. These forced sales pushed prices lower. More liquidations triggered. Spreads widened from 0.02 basis points to 26.43 basis points—a 1,321x explosion—as market makers withdrew [21].

The worst casualties occurred on illiquid assets where the spot order book was paper-thin. On Binance, ATOM briefly traded at $0.001—a 99.96% crash—because there were simply no bids in the book [22]. Traders with leveraged positions on these assets were liquidated at prices that bore no relationship to fundamental value.

Hyperliquid, a decentralized perpetual futures exchange, processed $10.31 billion in liquidations—more than Binance and Bybit combined [23]. The platform activated its auto-deleveraging system for the first time in years, forcibly closing profitable positions to offset losses from bankrupt accounts. Market maker ABC lost $35 million in a single night—73% of their account [24].

Here is where 2025 diverged catastrophically from 1907. In the earlier crisis, Morgan had time—days, even weeks—to organize rescues, examine books, and coordinate interventions. The crypto cascade completed in hours. $3.21 billion vanished in a single 60-second window [25].

More fundamentally, there was no coordination mechanism. Exchanges competed rather than cooperated. When Binance's infrastructure failed between 20:50 and 22:00 UTC, no one organized emergency liquidity provision [26]. Automated liquidation engines executed without human discretion. A whale with $1.1 billion in short positions profited an estimated $190-200 million while retail traders were obliterated [27].

Morgan chose which institutions to save and which to let fail based on careful analysis of their books. In 2025, algorithms made no such distinctions. The solvent and insolvent alike were liquidated at whatever price the thin order book would bear.

The Sagix lessons: building portfolios that don't need rescue

The 1907 Panic led directly to the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913—an institutional response to the realization that private coordination, however heroic, was insufficient for a modern economy [28]. Whether October 2025 produces equivalent innovation in crypto markets remains to be seen.

For individual investors, however, the lessons are immediately applicable.

Lesson 1: Leverage transforms recoverable drawdowns into permanent losses.

The people liquidated on October 10, 2025 may have been correct about their long-term thesis. Bitcoin recovered. Ethereum recovered. But being right on a six-month horizon means nothing if you're liquidated on a six-minute horizon. At 20x leverage, a 5% adverse move wipes you out. At 50x, a 2% move does. The traders who survived October 10 were those who owned assets outright rather than through leveraged derivatives [29].

Lesson 2: Liquidity is not guaranteed—and disappears precisely when you need it most.

Both 1907 and 2025 demonstrated that liquidity is a collective illusion that evaporates in crisis. The market makers who provide tight spreads during normal times step away when volatility spikes. The order book depth you see today may not exist tomorrow. The bid you're counting on to exit your position is someone else's decision to make—and in a panic, they may decide not to make it [30].

Lesson 3: Your position is only as good as the infrastructure supporting it.

Trust company depositors in 1907 discovered that their claims depended on institutions outside the regulated banking system with no access to emergency facilities. Crypto traders in 2025 discovered that their positions depended on exchange infrastructure that could fail, oracles that could be manipulated, and collateral that could depeg. Binance's USDe stablecoin traded at $0.65 on its platform while maintaining $1.00 everywhere else—and positions collateralized with USDe were liquidated based on Binance's internal price [31].

Lesson 4: The absence of coordination mechanisms means you must be your own Morgan.

Morgan could rescue institutions because he had capital, relationships, and authority. Retail traders have none of these. In a market without a lender of last resort, without circuit breakers, without coordinated intervention, you cannot rely on rescue. The Sagix philosophy therefore emphasizes positions that don't require rescue—unleveraged holdings in liquid assets that can weather drawdowns without forced liquidation.

Lesson 5: The patterns repeat because human nature doesn't change.

Trust companies in 1907 grew explosively because they offered higher returns through regulatory arbitrage. DeFi protocols grew explosively for the same reason. Speculators in both eras used leverage to amplify gains, assuming liquidity would always be available to exit. The Heinze brothers' copper corner and the October 2025 whale's billion-dollar short represent the same impulse: exploit a fragile system for personal gain, regardless of systemic consequences.

The 118 years between these crises produced technological transformation but not structural immunity. An initial manipulation estimated at $60 million cascaded into $19.3 billion in liquidations—a 322x amplification factor [32]. The mechanisms evolve; the vulnerabilities persist.

For those building durable wealth across decades, the lesson is clear: own assets rather than claims on assets. Avoid leverage. Maintain liquidity buffers. And never assume that someone will lock the bankers in the library to save you—because in modern markets, the bankers are algorithms, and the library doesn't exist.

Sources and references

[1] Federal Reserve History. "The Panic of 1907." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/panic-of-1907

[2] Wikipedia. "Panic of 1907." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panic_of_1907

[3] Moen, Jon and Ellis Tallman. "The Panic of 1907." EH.net Encyclopedia. https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-panic-of-1907/

[4] Frydman, Carola and Ellis Hilt. "The Panic of 1907: JP Morgan, Trust Companies, and the Creation of the Fed." NBER Conference Paper, 2012.

[5] Federal Reserve History. "The Panic of 1907."

[6] Federal Reserve History. "The Panic of 1907." (Trusts provided uncollateralized loans that nationally chartered banks were prohibited from making.)

[7] Moen and Tallman. "The Panic of 1907." EH.net.

[8] History.com. "The Financial Panic That Gave Birth to the Federal Reserve." https://www.history.com/articles/federal-reserve-bank-origins-history

[9] EBSCO Research Starters. "Panic of 1907." https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/panic-1907

[10] Federal Reserve History. "The Panic of 1907." (Benjamin Strong's role in assessing Knickerbocker.)

[11] Wikipedia. "Panic of 1907." (Trust Company of America rescue details.)

[12] Federal Reserve History. "The Panic of 1907." (Moore & Schley crisis and TC&I acquisition.)

[13] Gotham Center for New York City History. "The Panic of 1907: How J.P. Morgan Took Over Wall Street." https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/the-panic-of-1907-how-jp-morgan-took-over-wall-street

[14] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. "The Panic of 1907: J.P. Morgan and the Money Trust." Educational Lesson Plan.

[15] Federal Reserve History. "The Panic of 1907." (Clearinghouse loan certificate issuance.)

[16] Andrew, A. Piatt. "Substitutes for Cash in the Panic of 1907." Quarterly Journal of Economics 23 (August 1908): 497-516.

[17] Ali, Zeeshan. "Anatomy of the Oct 10–11, 2025 Crypto Liquidation Cascade." SSRN Working Paper, abstract_id=5611392. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5611392

[18] Bloomberg. "Trump Tariffs Upend Crypto Market, Trigger Record Liquidations." October 10, 2025. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-10-10/crypto-sees-more-than-3-billion-in-liquidations-in-past-hour

[19] Bernanke, Ben. "The Crisis as a Classic Financial Panic." Speech, November 8, 2013. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20131108a.htm

[20] CCN. "Perpetual Futures Dominate Crypto Trading Volume." https://www.ccn.com/analysis/technology/perpetuals-account-majority-crypto-market-behavior/

[21] Amberdata. "How $3.21B Vanished in 60 Seconds: October 2025 Crypto Crash Explained Through 7 Charts." November 5, 2025. https://blog.amberdata.io/how-3.21b-vanished-in-60-seconds-october-2025-crypto-crash-explained-through-7-charts

[22] Phemex News. "ATOM Price Glitch on Binance: No Impact on Liquidations." October 2025. https://phemex.com/news/article/atom-spot-price-on-binance-briefly-hits-0001-no-impact-on-liquidations-26464

[23] CoinDesk. "'Largest Ever' Crypto Liquidation Event Wipes Out 6,300 Wallets on Hyperliquid." October 11, 2025. https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2025/10/11/largest-ever-crypto-liquidation-event-wipes-out-6-300-wallets-on-hyperliquid

[24] Bitget News. "The largest liquidation in crypto history: Who suffered the most losses?" October 2025. https://www.bitget.com/news/detail/12560605010983

[25] Amberdata. "How $3.21B Vanished in 60 Seconds."

[26] CryptoRank. "The October 11, 2025 Crypto Market Crash: Situation Overview." https://cryptorank.io/insights/analytics/crypto-market-crash-2025-10-11-overview

[27] Investing.com. "The Crypto Crash and the Mystery of the $1 Billion Whale." October 2025. https://www.investing.com/analysis/the-crypto-crash-and-the-mystery-of-the-1-billion-whale-200668895

[28] Federal Reserve History. "The Panic of 1907." (Connection to Federal Reserve creation.)

[29] Coinbase. "Key Strategies to Avoid Liquidations in Perpetual Futures." https://www.coinbase.com/learn/perpetual-futures/key-strategies-to-avoid-liquidations-in-perpetual-futures

[30] The Coinomist. "ADL Mechanism on Crypto Exchanges: How Forced Liquidation of Profitable Positions Works." https://thecoinomist.com/learn/adl-mechanism-crypto-exchanges-liquidation/

[31] Brave New Coin. "USDe Depeg on Binance: Was It a Coordinated Attack?" October 2025. https://bravenewcoin.com/insights/usde-depeg-on-binance-was-it-a-coordinated-attack

[32] CCN. "Was the October 2025 Crypto Crash a Coordinated Attack? Here's the Truth." October 13, 2025. https://www.ccn.com/education/crypto/october-2025-crypto-crash-coordinated-attack-onchain-evidence/

Legal disclaimers and disclosures

Educational purpose only: This content is provided exclusively for educational and historical research purposes. It should not be construed as investment advice, financial planning guidance, policy recommendations, or official economic analysis. Any contemporary parallels or policy discussions are presented as academic analysis, not recommendations for action. Historical patterns provide context for learning but do not predict future financial system outcomes or investment performance.

AI-assisted research disclosure: This historical analysis was researched and written with substantial assistance from artificial intelligence technology (Claude, Anthropic). While extensive efforts were made to verify all statistical claims, citations, and institutional analysis against authoritative sources, readers should independently verify any information before relying on it for academic, professional, investment, or policy purposes.

Accuracy and liability limitations: While extensive effort has been made to ensure historical accuracy through authoritative sources, the authors make no warranties about completeness, accuracy, or currency of information. Historical interpretation involves scholarly judgment and academic debate. Economic data may contain revisions, measurement inconsistencies, or reporting variations across different time periods and institutional sources.

Liability protections: The authors, publishers, and Sagix Apothecary assume no responsibility for errors, omissions, or consequences arising from the use of this information. This includes any errors that may result from AI assistance in research, writing, or data analysis. Users assume full responsibility for any decisions or actions taken based on this content.

Investment risk warning: Historical financial analysis does not constitute investment advice or recommendations. Past performance, whether historical or hypothetical, does not guarantee future results. All investments carry risk of loss, and readers should conduct their own research and consult qualified financial advisors before making investment decisions.

No professional relationship: This content does not create any professional, advisory, fiduciary, or client relationship between the reader and Sagix Apothecary, its authors, or affiliated entities. Readers seeking financial, investment, legal, regulatory, or policy guidance should consult qualified professionals licensed in their jurisdiction.

Methodological note: This analysis synthesizes findings from multiple Federal Reserve Bank research departments, National Bureau of Economic Research publications, peer-reviewed academic journals, and authoritative government historical records. The numbered citation system allows readers to verify specific claims against original sources rather than relying on secondary interpretations. All quantitative data and statistical analyses are drawn from the referenced academic literature rather than independent calculation.

Contemporary financial systems: References to modern financial systems, cryptocurrency protocols, or DeFi mechanisms are made for educational comparison purposes only. These comparisons do not constitute endorsements, recommendations, or predictions about the performance or suitability of any current financial products or services.

Crisis analysis: Historical analysis of financial crises is provided for educational understanding of systemic risk patterns. This content does not predict future crises or recommend specific crisis preparation strategies. Readers should consult qualified professionals for personalized risk management advice.

Publication information: Last Updated: December 2025 | Series: The Druid Deep Dive | Publisher: The Genesis Address LLC

Ancient wisdom for modern DeFi — The Druid Deep Dive